i_need_contribute

i_need_contribute

Choi Seung-hoon thought he had an impossible assignment. On a grey autumn day in Beijing in 2004, he embarked on a marathon effort to get a couple of dozen representatives from Asian nations to boil down thousands of years of knowledge about traditional Chinese medicine into one tidy classification system.

Because practices vary greatly by region, the doctors spent endless hours in meetings that dragged over years, debating the correct location of acupuncture points and less commonly known concepts such as ‘triple energizer meridian’ syndrome. There were numerous skirmishes between China, Japan, South Korea and other countries as they vied to get their favoured version of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) included in the catalogue. “Each country was concerned how many terms or contents of its own would be selected,” says Choi, then the adviser on traditional medicine for the Manila-based western Pacific office of the World Health Organization (WHO).

But over the next few years, they came to agree on a list of 3,106 terms and then adopted English translations — a key tool for expanding the reach of the practices.

And next year sees the crowning moment for Choi’s committee, when the WHO’s governing body, the World Health Assembly, adopts the 11th version of the organization’s global compendium — known as the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). For the first time, the ICD will include details about traditional medicines.

The global reach of the reference source is unparalleled. The document categorizes thousands of diseases and diagnoses and sets the medical agenda in more than 100 countries. It influences how physicians make diagnoses, how insurance companies determine coverage, how epidemiologists ground their research and how health officials interpret mortality statistics.

The work of Choi’s committee will be enshrined in Chapter 26, which will feature a classification system on traditional medicine. The impact is likely to be profound. Choi and others expect that the inclusion of TCM will speed up the already accelerating proliferation of the practices and eventually help them to become an integral part of global health care. “It will definitely change medicine around the world,” says Choi, now the board chair of the National Development Institute of Korean Medicine in Gyeongsan.

Whether this is a good thing depends on whom you talk to. For Chinese leaders, the timing could not be better. Over the past few years, the country has been aggressively promoting TCM on the international stage both for expanding its global influence and for a share of the estimated US$50-billion global market.

Medical-tourism hotspots in China are drawing tens of thousands of foreigners for TCM. Overseas, China has opened TCM centres in more than two dozen cities, including Barcelona, Budapest and Dubai in the past three years, and pumped up sales of traditional remedies. And the WHO has been avidly supporting traditional medicines, above all TCM, as a step towards its long-term goal of universal health care. According to the agency, traditional treatments are less costly and more accessible than Western medicine in some countries.

Many Western-trained physicians and biomedical scientists are deeply concerned, however. Critics view TCM practices as unscientific, unsupported by clinical trials, and sometimes dangerous: China’s drug regulator gets more than 230,000 reports of adverse effects from TCM each year.

With so many questions about TCM’s effectiveness and safety, some experts wonder why the WHO is increasing support for such practices. One of them is Donald Marcus, an immunologist and professor emeritus at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and a prominent TCM critic. In his opinion, “at some point, everyone will ask: why is the WHO letting people get sick?”

A pharmacy in a traditional-medicine hospital in Beijing dispenses medications.Credit: David Gray/Reuters

TCM is based on theories about qi, a vital energy, which is said to flow along channels called meridians and help the body to maintain health. In acupuncture, needles puncture the skin to tap into any of the hundreds of points on the meridians where the flow of qi can be redirected to restore health. Treatments, whether acupuncture or herbal remedies, are also said to work by rebalancing forces known as yin and yang.

Practitioners of TCM and Western-trained physicians have often eyed each other suspiciously. The Western convention is to seek well-defined, well-tested causes to explain a disease state. And it typically requires randomized, controlled clinical trials that provide statistical evidence that a drug works.

From the TCM perspective, this is too simplistic. Factors that determine health are specific to individuals. Drawing conclusions from large groups is difficult, if not impossible. And the remedies are often a mix of a dozen or more ingredients with mechanisms that cannot, they say, be reduced to a single factor.

There has, however, been something of a détente. Organizations steeped in the Western conventions, such as the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), have created units to research traditional medicines and practices. And TCM practitioners are increasingly looking for proof of efficacy in clinical trials. They often speak of the need to modernize and standardize TCM.

Chapter 26 is meant to be a standard reference that all practitioners can use to help diagnose disease and assess possible causes. For example, ‘wasting thirst syndrome’ is characterized by excessive hunger and increased urination and explained by “factors which deplete yin fluids in the lung, spleen or kidney systems and generate fire and heat in the body”. On the basis of those observations, physicians can work out how to treat them. The patient, who would probably be diagnosed as diabetic by a Western doctor, would probably be prescribed acupuncture, various tonics and moxibustion — in which practitioners burn herbs near the skin of the patient. Spinach tea, celery, soya beans and other ‘cooling’ foods would also be recommended.

TCM practitioners around the world are gearing up for Chapter 26, which is set to be implemented by WHO member states in 2022. “For the first time in history, ICD codes will include terminology such as Spleen Qi Deficiency or Liver Qi Stagnation,” reads a post on the website of Five Branches University, a TCM training and research institution based in San Jose, California, which worked with the WHO on a field trial of the diagnostic criteria in Chapter 26.

A patient is treated with heated cups at a traditional-medicine clinic in south China’s Hainan Province.Credit: Xinhua/Avalon.red

Critics argue that there is no physiological evidence that qi or meridians exist, and scant evidence that TCM works. There have been just a handful of cases in which Chinese herbal treatments have proved effective in randomized controlled clinical trials. One notable product that has emerged from TCM is artemisinin. First isolated by Youyou Tu at the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Beijing, the molecule is now a powerful treatment for malaria and won Tu the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015.

But scientists have spent millions of dollars on randomized trials of other TCM medicines and therapies with little success. In one of the most comprehensive assessments, researchers at the University of Maryland school of medicine in Baltimore surveyed 70 systematic reviews measuring the effectiveness of traditional medicines, including acupuncture. None of those studies could reach a solid conclusion because the evidence was either too sparse or of poor quality1. The NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health in Bethesda, Maryland, concludes that “for most conditions, there is not enough rigorous scientific evidence to know whether TCM methods work for the conditions for which they are used”.

In response to queries by Nature, the WHO said that its Traditional Medicine Strategy “provides guidance to Member States and other stakeholders for regulation and integration, of safe and quality assured traditional and complementary medicine products, practices, and practitioners”. It emphasized that the goal of the strategy “is to promote the safe and effective use of traditional medicine by regulating, researching and integrating traditional medicine products, practitioners and practice into health systems, where appropriate”.

China’s support of TCM started with former leader Mao Zedong, who reportedly didn’t believe in it but thought it a could reach under-served populations. Current Chinese President Xi Jinping has strongly supported TCM and, in 2016, the powerful state council developed a national strategy that promised universal access to the practices by 2020 and a booming industry by 2030. That strategy includes supporting TCM tourism, which steers large numbers of people to clinics in China. Every year, tens of thousands of mostly Russian tourists flock to Hainan off the southern coast seeking relief through TCM. The government has plans to build 15 TCM ‘model zones’ similar to the one in Hainan by 2020.

The country also has global ambitions. China’s Belt and Road trade initiative calls for creating 30 centres by 2020 to provide TCM medical services and education, and to spread its influence. By the end of 2017, 17 centres had sprung up in countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Hungary, Kazakhstan and Malaysia.

The ties are paying off. Sales of TCM herbal medicines and other related products exported to Belt and Road countries surged by 54% between 2016 and 2017, to a total of US$295 million.

The WHO’s support applies to all traditional medicines, but its relationship with Chinese medicine, and with China, has grown especially close, in particular during the tenure of Margaret Chan, who ran the organization from 2006 to 2017. In Beijing in November 2016, Chan gave an address full of praise for China’s advances in public health and its plans to spread traditional medicine. “What the country does well at home carries a distinctive prestige when exported elsewhere,” she said.

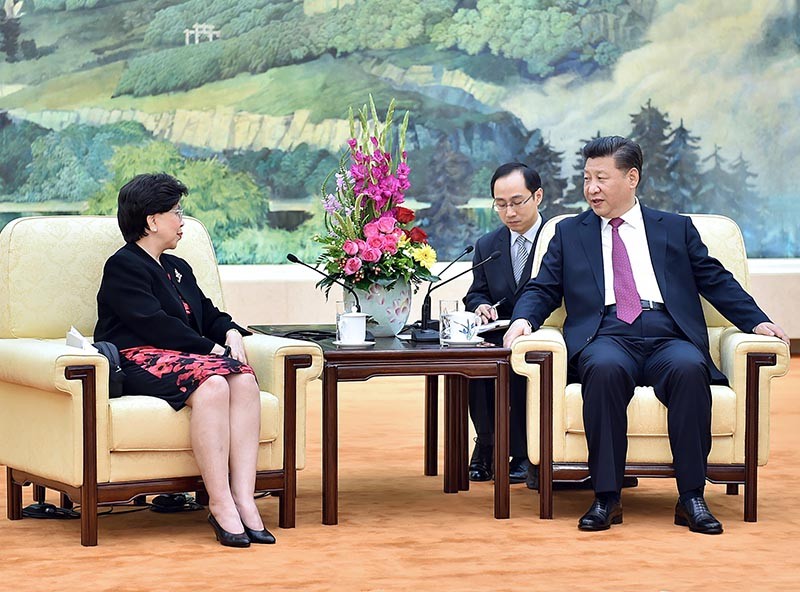

During a meeting in Beijing in 2016, China’s president Xi Jinping talks with Margaret Chan, then director-general of the World Health Organization.Credit: Xinhua/Photoshot

Chan has supported traditional medicines, and specifically TCM, and has worked closely with China to promote this vision. In 2014, the WHO released a ten-year strategy that aims to integrate traditional medicines into modern medical care to achieve universal health coverage. The document calls on member states to develop health-care facilities for traditional medicine, to ensure that insurance companies and reimbursement systems consider supporting traditional medicines and to promote education in the practices.

In the same year, Chan wrote an introduction to a supplement that ran in Science and was sponsored by the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine and Hong Kong Baptist University2. (Nature ran a similar paid-for supplement in 2011.) Chan wrote that traditional medicines are “often seen as more accessible, more affordable, and more acceptable to people and can therefore also represent a tool to help achieve universal health coverage”. In a 2016 speech in Singapore, Chan said that TCM has excelled at preventing or delaying heart disease because it “pioneered interventions like healthy and balanced diets, exercise, herbal remedies and ways to reduce everyday stress”.

But many Western physicians and scientists doubt that the herbal remedies and various other components of TCM or other traditional medicines have much to offer in their current use. They grant that TCM herbs might turn up useful molecules (many Western drugs are derived from plants, after all), but worry that TCM could replace proven drugs or be potentially dangerous.

Arthur Grollman, a cancer researcher at Stony Brook University in New York, has published work showing how aristolochic acid, an ingredient in many TCM remedies, can cause kidney failure and cancer3. He thinks that WHO documents should pay more attention to the risks of remedies that contain the chemical, which are still widely used.

For some scientists, the WHO’s embrace of TCM is perplexing. “I thought the WHO was committed to evidence-based medicine,” says Richard Peto, a statistician and epidemiologist at the University of Oxford, UK.

Many physicians and researchers also find the WHO’s declarations about traditional medicine hard to parse. Various WHO documents call for the integration of “traditional medicine, of proven quality, safety and efficacy”. But the agency does not say which traditional medicines and diagnostics are proven. Wu Linlin, a WHO representative in the Beijing office, told Nature that the “WHO does not endorse particular traditional and complementary medicine procedures or remedies”.

But that stands in sharp contrast to the WHO’s actions in other areas. The agency gives member countries specific advice on what vaccines and drugs to use and what foods to avoid. With traditional medicines, however, the specifics are mostly omitted. The WHO website carries some warnings and states that aristolochic acid is a carcinogen. But with the repeated emphasis on integrating traditional medicine, the message is clear, says Marcus. In his view, “the WHO is clearly saying these are safe and effective medicines”.

Nature tried to contact Chan multiple times through the WHO, but the agency says that she is not answering questions on matters related to the WHO.

Despite the concern over the WHO’s decision to include TCM, even critics of the practices say that Chapter 26 could serve a constructive purpose. Peto says that Chapter 26 could help researchers to gather data on adverse reactions and what kinds of traditional treatments people are getting. “But if the aim is to endorse these things, it is inappropriate,” he says.

For those steeped in Western medicine, the continued spread of traditional treatments is worrisome. TCM practitioners increasingly talk of replacing proven Western medicines with traditional substitutes, where there is a cost advantage. Grollman thinks that ICD-11 is heading in that direction. Seventy per cent of money spent on health care globally is reimbursed or allocated on the basis of ICD information. Now TCM will be part of that system.

“The thing they want is to make it sound official and be recognized by the insurance companies. Because it’s relatively low cost, insurance companies will accept it,” says Grollman.

Many others agree that the WHO’s decision will help the spread of TCM. Inclusion in ICD-11 is “a powerful tool for [health-care] providers to say this is legitimate medicine” to insurers, says Ryan Abbott, a medical doctor who has also trained in TCM and is a faculty member at the University of California, Los Angeles, Center for East–West Medicine. The WHO’s action regarding TCM, he says, “is a mainstream acceptance that will have significant impact around the world”.

Nature 561, 448-450 (2018)

doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-06782-7

Manheimer, E. et al. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 15, 1001–1014 (2009).

Chan, M. Science 346, S2 (2014).

3.Grollman, A. P. et al. Adv. Mol. Toxicol. 3, 211–227 (2009).